Culture Connection Resurgence

At the Mastercard Foundation, through our EleV initiative, we listen to and work closely with Indigenous youth. We are fortunate to regularly see and hear about Indigenous youth leading in their communities, but also know all too well the continued challenges Indigenous youth experience in Canada.

As a result, EleV in partnership with Indigenous youth, leaders, and institutions aims to shift systems to better enable Indigenous youth to lead, pursue their aspirations, and contribute to their communities.

Focused on supporting Indigenous learners through post-secondary and onto work, EleV is grounded in youth visions of Mino-Bimaadiziwin (living a good life). The name EleV draws inspiration from the “flying V” formation common to geese and other migratory birds, reflecting that leadership is an unselfish act, shared by many, in pursuit of a greater purpose.

This book celebrates and elevates young Indigenous artists, their artwork, and their vision for the future. It also demonstrates how complex the challenges are that Indigenous young people face today, and the multitude of inspiring approaches youth are taking in response.

We invited young Indigenous artists to respond to a question: “What does Mino Bimaadiziwin (living a good life) mean to you?” Together, the art and statements shared in this book, act as a call to action and urge us to recognize the importance of reclaiming Indigenous wisdom and, along with Indigenous youth themselves, let that wisdom guide a new era of transformation.

Chief Lady Bird

Love Your Indigenous Foods, Love Your Indigenous Lands, Love Your Indigenous Self

Chief Lady Bird is a Chippewa and Potawatomi artist from Rama First Nation and Moosedeer Point First Nation, who is currently based in Toronto, ON. She graduated from OCAD University in 2015 with a BFA in Drawing and Painting and a minor in Indigenous Visual Culture. Through her art practice, Chief Lady Bird uses street art, community-based workshops, digital illustration and mixed media work to empower and uplift Indigenous people through the subversion of colonial narratives, shifting focus to both contemporary realities and Indigenous Futurisms by creating space to discuss the nuances of our experiences.

Fluent, velvety Ojibway

With so many syllables, you could get lost in the sounds

Echoing, leaping and dancing from my lips.

Words that have been begging to escape the confines of my teeth

And hot breath

My entire life.

Even when the language hasn’t fully shown itself,

It has always been there.

Dormant, pacing, biding its time

Like a mischievous trickster

Scheming

About how to catch the ducks.

Or like a

rumbling volcano,

Ready to erupt and spill its power onto colonized lands.

I imagine a world where we use the language to truly feel

Everything.

— Chief Lady Bird

Mariah Meawasige

Mariah Meawasige (Makoose) is an Anishinaabe/settler and creative from the northern shores of Lake Huron. Her practice specializes in graphic design but questions the bounds of communication through illustration, sculpture, video, and performance. Through her love of stories and storytelling, Mariah’s body of work aims to explore temporalities and place, map memories, and build relationships.

“To me, Mino Bimaadiziwin is a state of deep connection and listening that feeds our past and future ancestors. We are constantly surrounded by teachers (in stories and beings, two- legged and four-legged and finned) who are prepared to share their stories; their section of the path. Having the courage and respect to listen through language, interactions, food, etc. – is making the decision to listen to those who have come before you and work for those who will come after. Building meaningful connections (to people, land, animals, objects, stories, etc.) has been foundational in my growth. Mno is an embodiment of the bliss found in pure, timeless, and intense connections with others.”

Audie Murray

Audie Murray is a multi-disciplinary Métis artist from Regina, SK, treaty 4 territory. She is currently learning and creating on the unceded territories of the Lekwungen peoples (Victoria). She has completed a visual arts diploma at Camosun College in 2016 and a Bachelor of Fine Arts at the University of Regina in 2017. Audie works with various materials including beadwork, quillwork, textiles, repurposed objects, drawing, performance and video. Her art practice is process oriented and explores overarching themes of contemporary Indigenous culture, duality and connectivity with the presence of medicine, healing and growth.

“Half son is a term that has been used to describe Michif people- âpihtawikosisân. These gloves are a comment about the labours of cultural identity. The Michif identity is thought of as two separate halves when in fact the Michif identity is a whole. This is stitched into the gloves as two half flowers. The flowers represent half sons while also representing half suns like a sunrise or sunset. They are brilliantly bright while also being an important part of something complete. To live in a good way is to listen to your heart and honour yourself. To live in a good way is to tell the stories that need to be told, when it is right to tell them.”

Blake Lepine

Blake Nelson Lepine or Shaá’koon, was born and raised in Whitehorse, YK. There’s a beautiful mixture of heritage in his background, he descends from Tlingit, Han, Cree and Scottish decent. The Tlingit artwork spoke to him from an early age, and being surrounded by the artists within his family, has inspired him to start drawing from a young age. Many hours have been spent practicing and perfecting his own stylized form and interpretation of this art to give a modern voice to an ancient art, but also branching it into modern mediums other than the traditional forms of carving and painting of his ancestors.

“Mino Bimaadiziwin means to me living in balance with all creation. To find the path where everything is honoured as sacred. When we allow ourselves the space to be open to the magic all around us, I feel that we’re living in a good way. When we honour the traditions left for us from our ancestors we are living in a good way. When we break free from the traumas that once plagued our everyday lives we are living in a good way. When we learn to love every path this life has to offer and give space for others to live theirs we are living in a good way. When we learn to truly love ourselves and remember that it’s ok to not love some parts of yourselves and strive for that strength in spirit to make yourself better, we are living in a good way.”

Brent Hardisty

Brent Hardisty is a Woodland style painter from Sagamok First Nation who works in acrylic on canvas. His spiritual name is Niiwin Binesi, which means that he represents and speaks for the winged ones. He lived in the city of Toronto in his earlier years and was highly influenced by the graffiti subculture. He eventually made a name for himself within that scene and moved onto painting murals for organizations and businesses.

“Youth Building Lodge could be interpreted in two different ways, either small young people building a sweat lodge or older youth building a Midewiwin lodge. The process of building the lodge is an important part of the ceremonies that take place within them. The process is communal, and it demonstrates the importance of community in ensuring spiritual, physical, and mental well-being. It is important that we all work together, youth and Elders alike, to maintain our sacred ways ensure balance in life. This is what Mino Bimaadiziwin is about, letting our teachings guide us into the future.”

Emily Kewageshig

Emily Kewageshig is an Ojibwe Woodland Artist. She was born and raised in Saugeen First Nation #29, a small reserve located along the shores of Lake Huron in Ontario. From a young age she was always creating art and found inspiration in her Anishinaabe culture and the natural environment she grew up in. Her work focuses on the relationships between people, animals, and is a connection back to the land.

Three Sisters by Emily Kewageshig

“To me, Mino Bimaadiziwin means the ability to lead a good life. It is my standard that I often refer back to when going through trials and tribulations in life. I often question myself: does the life I’m living reflect positively on my own Anishinaabe ways of being? Am I maintaining the seven grandfather teachings in all aspects of my life? These questions that I pose to myself, allow me to reflect on my journey through life, and they also give me motivation and purpose to live my truths in a good way.”

Luke Swinson

Luke Swinson is an Anishinaabe artist who is a member of the Mississaugas of Scugog Island First Nation and resides in Kitchener, ON. Cultural education, preservation, and progression are key factors in what drives Luke to create. His journey in understanding and reclaiming his Indigenous culture is reflected in his work. Having been raised around computers, Luke is primarily a digital artist and enjoys using non-traditional methods to express himself creatively.

“Mino Bimaadiziwin (Living in a good way) means to be mindful of everything around us. Makwa Dodem Healing portrays a young Indigenous woman healing her mind through a connection to her traditional clan and culture. In Anishinaabe culture, “Makwa Dodem” or “Bear Clan”, among other attributes, represents health and healing. The long, flowing hair signifies the growing spirit of the woman and her connection to all things.”

Emma Hassencahl-Perley

Emma Hassencahl-Perley is Wolastoqey (Maliseet) from Tobique First Nation, NB. She currently resides in Fredericton, NB, working as an emerging curator at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery, an instructor at the New Brunswick College of Craft and Design, and a practicing visual artist. Emma graduated from Mount Allison University in 2017 with a Bachelor of Fine Arts. Her work critiques the relationship between Indigenous Peoples and the settler state and society of Canada, as well as exploring legislative identity and her own identity as a Wolastoqey woman.

“I believe that living in a good way means living in good relations with myself, others, and the earth. Living in a good way means holding myself accountable because I am not a perfect person and other people are not perfect. Making art keeps me grounded in who I am and who I want to be: someone more loving, patient and kind. Art allows me to feel that I am contributing to my nation by continuing their visual history and identity. I live in a good way by respecting my traditions and ancestors. I live in a good way by seeking the truth in my work.”

Jordan Stranger

Through pencil, paint, or digital platforms, Jordan Stranger communicates the importance of life, culture and acceptance. Jordan’s works are deeply rooted in the traditions within contemporary Indigenous cultures. “Life is about happiness. My work is an example of searching for it.” As an Oji-Cree individual, Jordan uses his life experiences to drive his artistic passions. He obtained his diploma in Graphic Design at Red River College in 2012 and has worked in advertising for the past 7 years. He commits his evenings and weekends to his artwork and works within his community creating murals and hosting art workshops for youth and adults.

“What Mino Bimaadiziwin means to me is to live out the Seven Sacred Teachings as best you can. To be mindful of everyone and everything around you. To carry yourself with kindness and empathy for all living things. To honour your ancestry through cultural practice and to help others with it. Our people have endured and persevered through many hardships. Seize the opportunity we have today and take back what those sought to take; who you are.”

Kelli Clifton

Kelli Clifton was born and raised in Prince Rupert, BC. Her father is Gitga’at from the community of Hartley Bay and her mother is of European ancestry. A graduate from the University of Victoria’s Fine Arts program, Clifton later worked as an Aboriginal Youth Intern for both the British Columbia Arts Council and the First Peoples’ Cultural Council. Clifton returned north to attend the Freda Diesing School of Northwest Coast Art in Terrace, BC. Clifton has always been interested in using her artwork as a form of storytelling, especially in relation to her Ts’msyen language (Sm’algyax), her family’s history with food fishing and other traditional ways of harvesting food, her coastal upbringing and her experiences as a First Nations woman.

“It’s incredible to think that not too long ago, our people were banned from performing our traditional songs. It’s often said that our drums are the heartbeat of our people. If you’ve ever heard our drums, you know that you can indeed feel their loud beat in your chest. When I returned to Prince Rupert after living away for 8 years, I was finally able to witness our people performing our traditional songs again. It was a very emotional experience for me, one that helped solidify my decision to move back home. I was very inspired by the drum and quickly came to realize that I had never painted one before. Eagle Drum is my very first painted drum and will always remind me of this transitional time in my life. Ama diduuls (living in a good way) is all about honouring our ancestors”

Joshua Mangeshig Pawis-Steckley

Joshua Mangeshig Pawis-Steckley is an Ojibwe/settler from Barrie, ON. He is a member of Wasauksing First Nation and has been living in Vancouver, BC for the past 4 years. He is currently an Artist-in-Residence at Skwachay’s Lodge in downtown Vancouver. Joshua’s practice consists mostly of acrylic painting and illustration in the Woodland art style. He is a master screen-printer and has graduated from the Graphic Design program at the Nova Scotia Community College. He is currently working on illustrating children’s books for Groundwood books and Harper-Collins.

“Endaayaan means home in Anishinaabemowin. For me home is with my family. This painting depicts one of my favourite memories from living on my rez where we would come together in my Nan’s tiny kitchen and eat breakfast as a family. Everyone would show up. The warmth we would share, the moments, the laughter filled our hearts with love. This is home. This is Mino Bimaadiziwin in it’s humblest form.”

Monique Aura Bedard

Monique Aura Bedard is a Onyota’a:ka (Oneida) & French Canadian multidisciplinary artist, currently based in Tkaronto. She is a DTATI Candidate and graduated from the University of Lethbridge with a BFA (Studio Art) in 2010. Through her art practice, she aims to discuss art as healing, intergenerational healing, identity, empowerment, and mothering. She looks to the community to collectively explore personal storytelling and truth-sharing.

“I am inspired by stories, memory and healing, individually and collectively. Through my art, I aim to address intergenerational trauma in my own family, with an emphasis on intergenerational healing to communicate experiences from the inside out. To me, living in a good way is about living life from the heart and with a good mind. I believe that walking on the land with love and respect alongside all Nations and all relations is at the core of living in a good way. My art is my voice, my truth and an extension of who I am. I hope my art reaches others in a way that inspires thoughts and feelings igniting curiosity, reflection and self-love.”

Aija Komangapik

Aija Komangapik is a young Inuk artist who is currently attending Bishops University in the hope of following her dreams of becoming an art administrator. She likes to spend her time reading, drawing or doing anything outdoors.

“2 Women depicts living in a good way because one can lay any meaning on these two women that they want. Whether one sees a love between sisters, mother and daughter, friends or even lovers, I made it just vague enough so that the onlooker can decide. What really matters is the love that transcends whatever I meant this piece to be. Living in a good way just means that we care for and support our loved ones.”

Manuel Axel Strain

Manuel Axel Strain is a 2-spirit interdisciplinary artist with Musqueam/Simpcw/Syilx heritage based in the unceded territory of the Katzie/Kwantlen peoples. Although they have attended Emily Carr University of Art + Design they are more appreciative of the knowledge they have gained from their mother, father, siblings, cousins, aunts, uncles, nieces, nephews, grandparents, and ancestors. Strain uses their lived experience as a source of agency to investigate different ways of healing and knowing. Invested with personal and political histories, their practice includes painting, photography, sculpture, performance, and installation, through which mental and spiritual well-being take paramount significance. Strain’s work is mainly concerned with assimilation religion, spirituality, intergenerational trauma, and healing. Their goal is to move beyond the binary opposition of the colonizer and the colonized to establish new ontologies for First Nations identities.

“I am someone who has dealt with addictions and mental health issues in my life. When faced with the reality that I had a substance use issue there seemed to be two choices, to either live a healthier spiritual, mental, and physical life or continue down a destructive path towards a slow death. Six years ago, I chose to live a life substance-free for not only the betterment of my own health but also for the betterment of my family. When I began this healing journey, I had to acknowledge certain aspects of my identity had been neglected. As I searched inward to address some of these issues, I came to the realization that my story, my identity was not unique. I had to acknowledge the fact that colonization has and continues to drastically transform the lives of Indigenous peoples. Living in a good way to me means to love, heal, and take care of myself as well as the world around me.”

Lauren Crazybull

Lauren Crazybull is an Edmonton, AB based Blackfoot and Dene visual artist. Lauren’s most recent work has looked to explore the tension and power within portraiture by examining the subtle relationship between herself and the subjects she paints. In 2019, Lauren was appointed as Alberta’s first Artist in Residence. In 2018, she was awarded the McLuhan house year-long studio residency. Through her work, she understands that her creative power is a poignant way to assert her own humanity and advocate in diverse and subtle ways for the innate intellectual, spiritual, creative and political fortitude of Indigenous people.

“In Blackfoot we say “Iikaakiimaat”, it means “try hard” or “persevere”. I try to take that with me wherever I go and with whatever I do. To live in a good way I try to take care of myself so I can put more care into the world around me.”

Alanah Jewell

Alanah Jewell is bear clan from Oneida Nation of the Thames. Mainly working with digital and acrylic mediums, her work is centered on a mix of contemporary and Woodland style art. Her work reflects her commitment to learning her culture, and her passion for creating Indigenous presence in the city.

“Disconnection is real and needs to be mended – especially for our youth – in order to break the negative intergenerational cycles many of us feel. Much of my art reflects a path of reconnection. No line can be separate, alone, or isolated. Because no being is separate, alone or isolated if we are all actively trying to reconnect to our roots. We begin to recognize every person, animal, plant and ancestor as something close to us, and part of our lives in some way. Indigenous art is not always just an expression of creativity. For me, it is also an expression of our histories, the teachings I have been given, and the importance of these connections.”

Animikiik'otcii Maakaai

Animikiik'otcii is an artist and a mother, born and raised in Toronto, ON. Her roots are with the Anishinaabek Nation from Kitchenuhmaykoosib Inninuwug, on her fathers’ side and from her mom her ancestors hail from Wales.

“Mino Bimaadiziwin means having hopes and dreams that inspire you to live everyday in a way that brings you closer to those things that make you feel whole. Dancing shawl is something I have long aspired to do, and I remind myself of that everyday; it inspires me to make the choices that will get me to where I want to be. Living in a good way also means gradually shedding the layers of colonialism to remember who I am, where I come from, and who I came from.”

Digital drawing

Chrystal Sparrow is a descendant from the Musqueam First Nation’s located on the unceded Coast Salish territory of Vancouver, BC. She carries rich bloodlines from Musqueam (Coast Salish), Sechelt (Coast Salish), Cree (Treaty 6) and Esk’etemc (Shuswap). She is a third generation Coast Salish artist and carver; and a fourth generation fisherwoman who was traditionally mentored by her father Irving Sparrow. Chrystal works in both traditional and contemporary art forms with a unique feminine style of elegance and simplicity. Her works represents an art language of culture, family teachings and personal experiences that are lived through an Indigenous world view.

“My family are strong, intelligent and humorous people. We understand that cultural practices, fishing rights and self-determination are a part of our livelihood. My role as a Coast Salish artist and carver is to carry forward a significant tradition and practice. My work also shares history and dialogues on good and bad experiences faced by First Nation’s in Canada. For me living a good life means learning new things from Elders and family; and carrying oneself with respect and kindness.”

Dayle Kubluitok

Dayle Kubluitok is an emerging artist from Kangiqliniq (Rankin Inlet) who lives in Iqaluit, NU. She works predominately with graphic arts and illustration and is also a growing photographer. She works with Nunavut Arctic College on graphic design, and she won the 2019 Northwestel’s Directory Cover Art competition.

“When I was younger I remember my grandma, great uncles, and aunts telling me Inuit legends and myths and they always sounded like ghost stories. Living a good life to me means learning more about my culture and passing on our traditions to my family.”

Kaya Joan

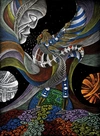

Kaya Joan is a multi-disciplinary Afro Caribbean (Jamaican/ Vincentian)-Indigenous (Kanien’kehá:ka/ Garifuna) artist living in T’karonto (Dish with One Spoon treaty territory). Kaya’s work focuses on healing, transcending ancestral knowledge and creating dreamscapes rooted in spiritualism from the lands of their ancestors (Turtle Island and the Caribbean). Afro and Indigenous futurity and pedagogy are also centred in Kaya’s practice working through buried truths to explore how creation can heal 7 generations into the past and future. Kaya has been working in community arts for 5 years as a facilitator and artist. Kaya is in the process of completing a BFA through the Indigenous Visual Culture program at OCAD.

“I will be well is a piece exploring how I heal through exploring and expressing intersections of the celestial (skyworld), the plant world, and water world. In this work I draw upon teachings of Ohén:ton Karihwatéhkwen, the words before all else, illustrating how everything is connected. I practice living in a good way by offering thanks and acknowledging the spirit and energy of all that surrounds me. This is a method of healing, which I express in this piece through colour and form, as well as overlaying the medicines, cedar, sage and tobacco. This layering and scanning process speaks to the interdimensionality of healing, and how it is not a linear process. To live in a good way, I must be well and in a process of healing, so I can show up for my family and community.”

Edwin Neel

Edwin Neel was born in Vancouver BC, has inhabited various cities on Vancouver Island, and currently resides in metro Vancouver. Neel has recently obtained a Bachelor of Fine Arts at Emily Carr University of Art + Design, spring 2017. Neel is a cultural producer of First Nations heritage, of the Kwagu’ł, and Ahousaht nations from his father and mother’s side respectively. Neel is formally trained and instructed in the Kwakwaka’wakw school of formline and carving by his father David Neel, an accomplished carver & jeweler.

“Mino Bimaadiziwin, or living in a good way can be interpreted as one navigating this world and interacting with it and its inhabitants and animals without ill intent and in a good-natured manner. The “way” is an agreeable understanding within the community of standard of conduct, not outright communicated, but generally understood.”

Keegan Starlight

Keegan Starlight is an Indigenous artist from the Tsuut’ina Nation in Southern Alberta. Starlight started practicing art 18 years ago and it has always been his passion, but he formally started his career during his time at Alberta University of the Arts (ACAD). Starlight has since gained skills in animation, design, 2D studio art, and art instruction. Starlight began exploring his art skills with drawing in various mediums such as pens, pencils, and charcoal. In 2008, Starlight started painting and has chosen to focus his skills in portrait paintings. His unique and creative eye for art has led him to try out new ideas that have diversified his skills.

“Living a healthy life to me consists of having a positive household and an open creative mind, eating healthy, and being active with my children and giving them their own creative freedom. Growing up on the Tsuut’ina Nation in a close-knit community has set me on the path of sharing the positivity and art that my family has gifted to me. My family and community taught me about the importance of accepting myself and that I have a responsibility to inspire others. Buffalo represents strength and stability. The buffalo is a visual representation of what healthy living looks like, a strong figure that helps to provide shelter, food, and tools.”

Hal Cameron

Hal Cameron is a multidisciplinary artist from the Beardy’s & Okemasis Cree Nation in Treaty 6 Territory. He has a passion for Language Revitalization and for telling stories through his work. He has been fortunate to create a style of work that allows him to portray his Cree Worldview and ties that into the promotion of language revitalization. He will continue sharing with others in this manner, in hopes to give others the insight to how Indigenous people see the world.

“Miyo Pimatisowin teaches me to share the values that have governed Indigenous people for generations. The artwork I create is rooted in a deeper meaning connected to living in a harmonious relationship with all things. Âsônamâkêwin - “Passing it on” tells the story of an Elder who has the sacredness of language flowing within her. As a fluent speaker it is their duty to share that gift, to nurture it, and allowing that sacredness to grow within our children. This piece is a reminder to those that still hold our Indigenous Languages to pass on that gift.”

Mitch Case

Mitch Case is a citizen of the Métis Nation and traces his family history across the upper Great Lakes and Southern Manitoba. Mitch is a beadworker who works in a traditional Métis floral style, and works to preserve and pass on the knowledge and skills of the art. Mitch was instrumental in creating the #beadworkrevolution, an online and community-based movement which has led to hundreds of young Métis people to learn to bead.

“Flowers, berries, leaves and stems, they shine, they shimmer - twist and turn. They reflect who we were, who we are; who we are forever becoming. As we bead, we tell stories: beautiful stories, painful stories, sacred stories and yes, some tall tales. We talk about the news and our latest Netflix favourites – because in spite of it all we are still here, still beading, still telling our stories. The good life is when we gather enough stories to put ourselves back together again, so we can be whole enough to create new stories to pass on.”