Executive Summary

Africa stands at a pivotal moment. Africa is home to the world’s fastest-growing generation of young talent. Today, Africa is home to around 532 million young people (aged 15–35), representing more than 22% of a cohort that will shape global labour in the coming decades. Unlike in the rest of the world, where youth populations are projected to continue declining, Africa’s youth population is expected to continue increasing through the 2070s.

Africa’s youth population is projected to grow by a record 132 million this decade (2020–2030), with an even larger increase of 147 million expected in the 2030s.

The continent has a rare opportunity to shape the future of global work. Realising this potential will depend on whether growth generates jobs, informal work becomes more productive and secure, young women are able to fully participate in labour markets, and education systems equip youth with skills aligned to a services-led economy.

The choices made today will determine whether Africa’s youth dividend becomes a foundation for shared prosperity.

The Africa Youth Employment 2026 Outlook provides insights on the state of youth employment across the continent, with a focus on how gender dynamics influence young people's access to work. It is the first in a series of reports aimed at deepening understanding of Africa’s evolving youth labour market. It builds on the Africa Youth Employment Clock, a labour market data model that tracks youth employment trends in Africa, (1) laying an analytical foundation for understanding these trends. The report is structured into two parts: Part 1. An overview of the state of youth employment; and Part 2. Gender trends with a focus on young women. This Africa Youth Employment Outlook is produced by the World Data Lab in partnership with the Mastercard Foundation and the University of Cape Town’s Development Policy Research Unit. This work is part of a broader effort to support the Mastercard Foundation’s Young Africa Works strategy, which seeks to enable 30 million young people in Africa, 70% of them young women, to access dignified and fulfilling work by 2030.

African governments have put the creation of high-quality jobs at the top of their development agenda and large global technology firms have taken note and expanded their footprint visibility. This renewed focus on Africa’s labour market and the skills of young people comes at a time when the continent’s young adults are undergoing three major shifts that will unfold in the coming decade.

Shift 1 - From working too early to studying.

Contrary to conventional belief, young Africans work more than their peers on other continents. About 57%, or 304 million youth in Africa, are estimated to be working as of 2025, compared with about 48% in the rest of the world. The number of employed youth on the continent is projected to increase to 437 million by 2040, though the share is expected to remain roughly stable at 58%.

At the same time, young Africans enter the labour market while still of school age (15–17) to take up predominantly low-paying, informal, agricultural work, often before completing their education. Among employed adolescents in this age group, educational attainment is low: around 42% have not completed primary education and a further 26% have completed only primary education.

As of 2025, nearly as many 15- to 17-year-olds were working as were studying. Among those working, 96% held informal jobs and 40% were living below the international poverty line of $2.15 a day (2017 PPP), with more than half employed in the agriculture sector. In this context, it is a misconception that unemployment is more widespread among young Africans than youth in the rest of the world(2). Low educational attainment, poverty, and a lack of social protection accelerate the school-to-work transition in low-income countries,(3) a transition that risks undermining long-term employment in more formal higher paying jobs.

Over the next decade, with rising education attainment and productivity gains in agriculture, it is projected that there will be more young Africans studying.

Shift 2 - From agriculture to services

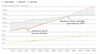

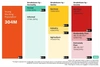

As of 2025, youth employment was still concentrated in agriculture, accounting for 47% of jobs, with about 143 million young Africans working in the sector. However, agriculture has a slower projected growth rate of 1.3 times (2015–2040) compared with the services sector (2.4 times). This means that by 2033 the services sector will employ more young Africans than the agriculture sector for the first time, with 3.8 million more workers.

Growth in the services sector is propelled by a combination of better income potential, urbanisation and broader structural economic changes, as some developing economies leapfrog manufacturing and shift labour directly from agriculture into services. Furthermore, as agriculture becomes more commercialized and shifts from diversified subsistence to cash-crop production, it increasingly involves trade, which in turn relies on services such as retail and logistics.

Across Africa, youth jobs in the services sector are more likely to be formal, at about 20%, compared with formality of just 11% of industry jobs and just 2% of agricultural jobs. In selected African countries analysed, young people working in services tend to earn more than those working in agriculture and industry. Where income data are reported, young people working in services earned about 2.6 times more than those in agriculture in 2024.

However, service roles are highly heterogeneous. Within the services sector, employment growth between 2015 and 2025 was strongest in accommodation and food service activities (+57%), and household-related employment (+54%), both of which are also the most female-dominated subsectors, with women accounting for 72% and 79% of employment, respectively.

By 2033, services will become the largest employer of young Africans, overtaking the long-dominant agriculture sector.

Shift 3 - From rural to urban.

Urbanisation is reshaping youth employment, with youth jobs shifting towards urban centres, accelerating the transformation from agriculture to services. In 2015, 35% of young Africans (85 million youth) worked in urban areas. In 2025, an estimated 38% of young Africans (115 million youth) worked in urban areas. In that period, urbanisation rates grew by 5 percentage points(4). While these three fundamental shifts play out over the coming decades, youth employment in Africa will face four major challenges. How these challenges are addressed will decide the degree to which Africa maximizes the opportunities presented to the continent by its growing young workforce.

Challenge 1 - Formal Job Creation. As we enter 2026, the labour markets of most African countries remain unbalanced, with economic growth failing to translate into sufficient job creation for youth. Each year, over 10 million young people enter the African labor market, yet current growth patterns are estimated to create only around 3 million formal jobs(5). To employ new labor market entrants by 2030, Sub-Saharan Africa alone will need to create an estimated 15 million new jobs annually(6).

The median youth employment elasticity,(7) a measure that indicates how much employment changes in response to a change in economic growth (GDP), shows that in certain countries, the employment elasticity for young women is higher than for men, in line with the global literature that finds female employment elasticities tend to be more volatile than those estimated for men,(8) shaped by a variety of factors such as the nature of a country’s economic growth, women’s sectoral employment composition, levels of informality, and their role in care work.

Sufficient job creation requires both an increase in the responsiveness of employment to growth and higher GDP growth rates than the estimated 3% in 2024. Africa’s economy suffered its first recession in 25 years with a 1.6% contraction in 2020, followed by a strong rebound to 6.9% in 2021, before slowing down again. Growth was tracking around 3.7% in 2024 and is expected to rise towards 4.0% in 2025–26.

Challenge 2 - Working Poverty.

Given that only about 10% of jobs are formal, Africa’s high employment rate fails to translate into economic security or job stability. High youth employment rates in Africa do not reflect job quality, with the majority of young workers concentrated in informal, low-paying employment.

While youth employment rates are high in countries such as Madagascar, Tanzania, and Ethiopia, 104 million of the 304 million young workers across the continent—about one in three—live in households categorized as extremely poor according to the international poverty line. In countries with higher youth employment rates, the share of employed young people living in extreme poverty is higher, and the link between high employment and high working poverty is particularly strong for young women. In addition, 90% of young, employed Africans (273 million) work in informal jobs. While some informal jobs, such as small-scale entrepreneurship, provide flexibility and autonomy, an overwhelming share of informal workers lack contracts, social protection, income stability, and prospects for career advancement.

The shift from agriculture to services as the primary employer for youth has a mixed impact on incomes, depending on the nature of the jobs. On one hand, the shift away from agriculture—a sector characterized by underemployment, low earnings, and income risk—offers opportunities for improved incomes due to higher productivity in services. However, a large share of emerging services jobs are informal with low productivity, limiting income improvement and perpetuating vulnerable employment.

Youth employment in Africa is primarily agricultural (47%) and informal (90%), while of the employed, 34% live in households below the international poverty line of $2.15 a day (2017 PPP).

Challenge 3 - Gender imbalance.

Young women continue to be more excluded from the labour market than young men. Women make up nearly 61% (62 million) of all youth not in employment, education, or training (NEET(9)). Unpaid care responsibilities remain a key constraint on women’s labour force participation: in Sub-Saharan Africa, 28% of women outside the labour force cite care responsibilities as their reason for non-participation, compared with only 3% of men(10).

While young women constitute a larger share of workers in Africa’s services sector (43% of employed young women work in services compared with 36% of young men in 2025), they are often concentrated in the most informal subsectors within services. Young men are gaining a larger share of employment in Africa’s fastest-growing sectors—industry and services—while young women’s share is rising in agriculture even as the sector itself declines.

This is in part attributable to gaps in higher education attainment levels that shift young people towards industry and services.

Challenge 4 - Skills.

Despite Africa’s economies shifting away from agriculture towards the services and industry sectors, which demand specialized skills, only 9% of young people have completed tertiary education as of 2025. This leaves most young Africans underprepared for the demands of a changing labour market. In some countries the challenge is not only too few graduates, but also what happens to those who do obtain tertiary education. For example, in some North African economies such as Algeria, Egypt, and Morocco, around 30% of young people with tertiary education are unemployed or inactive.

These trends are driven in part by insufficient job creation in the private sector,(11) a mismatch and inadequacy in skills acquired in school compared with those required at work,(12) and a gap between the expectations of educated job seekers and the quality of available jobs. Young women in North Africa face additional constraints, such as wage disparities, safety concerns and societal expectations regarding domestic duties (13).

Africa is fortunate in experiencing a considerable opportunity with the arrival of millions of young people into its workforce, just at a time when elsewhere in the world youth population is starting to decline. This is also timely given that the world, including Africa, is transitioning towards growing job opportunities in the services sector, especially as services become increasingly digital.

The most important question, therefore, is how African countries should best address the four main challenges outlined above.

First, in terms of job creation, African countries have an opportunity to focus on economic activities such as tourism, horticulture, and agro-processing, which have successfully absorbed young workers in countries such as Rwanda and Senegal (14). Because traditional manufacturing often faces costly bottlenecks in energy and logistics,(15) the digital services sector offers a unique opportunity for job growth as it faces fewer physical infrastructure constraints.

Additionally, rising public and private investment in infrastructure creates scope for construction-led employment growth.

Ethiopia's Urban Institutional and Infrastructure Development Program (2018-2024) financed the construction and rehabilitation of over 2,700 km of roads and 2,700 hectares of serviced land, creating 1.15 million jobs (915,000 temporary and 237,000 permanent), with women filling nearly half of these roles (16). Furthermore, promoting employment outside of capital cities, particularly as Africa becomes increasingly urbanised, can help ensure that job creation is geographically balanced as has been the case in Kenya rather than concentrated in capitals.

Second, in terms of formality, since 90% of young employed Africans currently work in informal jobs predominantly in the agriculture sector, an important strategy is to improve productivity and protections within the informal economy rather than focusing solely on the small formal sector. Kenya (17) (9% youth formality), Ethiopia (18) (12%), and Tunisia (19) (25%) have implemented health and social security schemes targeting informal and agricultural workers though more needs to be done to improve uptake and attrition. Furthermore, targeted support for the self-employed, including access to credit and business training, can help transform precarious micro-businesses into stable, productive entrepreneurship.

Rwanda (17% youth formality) and Ghana (9%) have implemented such targeted strategies. Rwanda's government supported over 31,000 households to establish businesses through entrepreneurship training and startup cash (20). Ghana's National Entrepreneurship and Innovation Programme aims to create at least 10,000 sustainable businesses annually with training, funding, and mentorship (21).

Third, addressing the gender gap requires dismantling systemic barriers, most notably unpaid care responsibilities, which are the primary reason young women remain outside the labor force. Policies should be implemented to redistribute the care burden and provide social protections that allow women to participate in the labor market. Rwanda, where 48.5% of young women are employed, Tanzania (76%) and South Africa (30%) have implemented targeted initiatives to address unpaid care responsibilities.

For instance, Tanzania committed at the 2021 Generation Equality Forum to increase investments in gender-responsive care services (22) and has opened over 3,000 Early Childhood Development centres on the mainland and 54 in Zanzibar (23). Furthermore, a durable transition of women into higher-productivity services such as ICT depends on keeping young women in school through secondary and tertiary education, alongside measures that reduce care burdens and other structural constraints.

For example, Namibia achieved the fastest growth in young women's contribution to GDP between 2017 and 2022 (40% to 42%) by enacting laws on property and asset rights, investing over 25% of the national budget in education, and mandating gender balance among teachers and decision-making bodies to ensure diverse role models. Across the continent, young women hold only 4% of construction jobs and 31% of industry jobs.

While women are generally underrepresented in industry, countries such as Niger, Togo, Benin, Nigeria, and Madagascar serve as positive outliers, where women make up over 48% of the industrial workforce. Legal constraints on asset ownership and limited access to land and credit significantly limit women's ability to participate in agriculture. For example, in Lesotho, young men comprise 77% of agricultural workers largely because they own critical assets like land and livestock. Finally, safeguarding education for young mothers is essential for high-productivity employment. Ethiopia provides a foundational example where the legal framework does not bar pregnant girls from education or work though the persistence of inactivity due to childcare responsibilities in the country highlights that legal permission alone is insufficient without stronger implementation and social protections.

Finally, in terms of education, systems must be urgently aligned with a labor market shifting towards services and industry. While tertiary education is a powerful predictor of formal employment and higher earnings, only about 9% of youth currently complete it. Governments should expand access to vocational training and advanced education while simultaneously addressing the mismatch between what is taught in schools and the specific skills demanded by the private sector.

Morocco has undertaken comprehensive reforms, with the Millennium Challenge Corporation's $450 million Morocco Employability and Land Compact investing in TVET programs by constructing and rehabilitating 15 TVET centers across Morocco to provide facilities and equipment in sectors including traditional artisan crafts, shipping and logistics, building trades, health services, and tourism, expected to benefit more than 800,000 Moroccans over 20 years (24). Strengthening social protections is also vital to prevent the premature exit of adolescents aged 15–17 from school into low-paying agricultural work.

With the world’s largest and fastest-growing youth population, the continent has a rare opportunity to shape the future of global work. Realising this potential will depend on whether growth generates jobs, informal work becomes more productive and secure, young women are able to fully participate in labour markets, and education systems equip youth with skills aligned to a services-led economy. The choices made today will determine whether Africa’s youth dividend becomes a foundation for shared prosperity.

Read the full Africa Youth Employment Outlook 2026 Report

References

- Any non-cited statistics are based on modelling from the Africa Youth Employment Clock.

- Mueller, Bernd. Rural Youth Employment in Sub-Saharan Africa: Moving Away from Urban Myths and Towards Structural Policy Solutions. International Labour Organization, 2021.

- Alam, Andaleeb, and Maria Eugenia de Diego. Unpacking School-to-Work Transition: Data and Evidence Synthesis. UNICEF, Aug. 2019, Scoping Paper No. 02.

- “Africa Population.” Worldometer, 2025, https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/africa-population/.

- World Bank. 2023. Delivering Growth to People through Better Jobs. Africa’s Pulse, No. 28 (October 2023). Washington, DC: World Bank. doi: 10.1596/978-1-4648- 2043-4.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2024. “The Clock is Ticking: Meeting Sub-Saharan Africa’s Urgent Job Creation Challenge.” In Regional Economic Outlook: Sub-Saharan Africa – Reforms amid Great Expectations. Washington, DC, October 2024.

- Employment elasticity is a measure that indicates how much employment changes in response to a change in economic growth (GDP). It is calculated as the percentage change in employment divided by the percentage change in GDP.

- Anderson, Bret & Braunstein, Elissa. (2013). Economic Growth and Employment from 1990-2010: Explaining Elasticities by Gender. Review of Radical Political Economics. 45. 269-277. 10.1177/0486613413487158.

- For analytical purposes, the official NEET indicator, internationally defined for ages 15–24, is extended in this report to include ages 25–35 using the same approach.

- ILO, 2024. The impact of care responsibilities on women’s labour force participation. Statistical Brief, International Labour Organization. October. Available: https://www.ilo.org/publications/impact-care-responsibilities-women%25s-labour-force-participation.

- World Bank. Overcoming Barriers to Youth Employment in Morocco. Washington, DC, World Bank, 2022.

- Pereira da Silva, Thomas. High and Persistent Skilled Unemployment in Morocco: Explaining it by Skills Mismatch. OCP Policy Center, November 2017.

- Assaad, Ragui, and Mohamed Ali Marouani, principal investigators. Jobs and Growth in North Africa 2020: Regional Report on. International Labour Organization, 2021.

- Richard, et al. Industries without Smokestacks: Industrialization in Africa Reconsidered. World Bank, 2018.

- McKinsey Global Institute. Africa at Work: Job Creation and Inclusive Growth. McKinsey Global Institute, Aug. 2012.

- "How an Urban Program in Ethiopia Delivered More than a Million Jobs." World Bank, 2 Sept. 2025, www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2025/09/02/ethiopia-urban

-institutional-and-infrastructure-development-program. Accessed 13 Jan. 2026. - Barasa, Edwine, et al. "Kenya National Hospital Insurance Fund Reforms: Implications and Lessons for Universal Health Coverage." Health Systems & Reform, vol. 4, no. 4, 2018, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7116659/. Accessed 13 Jan. 2026.

- "Community-Based Health Insurance Drives Ethiopia's Bid for Universal Health Coverage." WHO Regional Office for Africa, World Health Organization, www.afro.who.int/countries/ethiopia/news/community-based-health-insurance-drives-ethiopias-bid-universal-health-coverage. Accessed 13 Jan. 2026.

- Access to Social Protection by Immigrants, Emigrants and Resident Nationals in Tunisia." Migration and Social Protection in Europe and Beyond (Volume 3), edited by Jean-Michel Lafleur and Daniela Vintila, Springer, 2020, link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-51237-8_22. Accessed 13 Jan. 2026.

- Village Enterprise. "Fund for Innovation in Development." Village Enterprise, 2024, villageenterprise.org/blog/fund-for-innovation-in-development/. Accessed 13 Jan. 2026.

- "National Entrepreneurship and Innovation Programme." NEIP, Government of Ghana, neip.gov.gh/. Accessed 13 Jan. 2026.

- "Op-ed: Addressing Women's Unpaid Care Work - A Catalyst for Tanzania's Progress." UN Women Africa, africa.unwomen.org/en/stories/op-ed/2023/11/op-ed-addressing-womens-unpaid-care-work-a-catalyst-for-tanzanias-progress. Accessed 13 Jan. 2026

- UN Women Africa. “In East and Southern Africa, Care Is Everyone’s Business – and It’s Changing Lives.” UN Women | Africa, 23 Oct. 2025.

- "Vocational Training Centers in Morocco to Provide Workers with In-Demand Skills." Millennium Challenge Corporation, mcc.gov/blog/entry/blog-012622-training-centers-morocco/. Accessed 13 Jan. 2026.